Meet Aanchal Malhotra: The Girl Documenting Material Memories From The Subcontinent?s Shared Past

Aanchal Malhotra is documenting our subcontinent?s shared past with her book and digital museum of material memory. Here?s a special story on India?s 72nd Independence Day.

In 2013, Aanchal Malhotra, then doing her Masters in Fine Arts from Concordia University, Montreal, accompanied a journalist friend for a story he was doing on old houses to her maternal grandparents? home in North Delhi. And while the family talked about their past, out came some old items (a ghara or metallic vessel and a gaz or yardstick) that had been in the family?s possession as they moved from Lahore to Amritsar and then to Delhi, just before the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947.

?These two objects transported my grandfather?s brother to Lahore in a way I hadn?t imagined,? says Malhotra, describing the excavation of memories that unfolded in front of her that day. ?An object sometimes has no value, unless you put the value of experience to it. I?m speaking specifically of ordinary, mundane objects that are now old and not considered conventionally valuable and expensive.?

That realisation led to a multidisciplinary project that Malhotra says has taken up the better part of her 20s. She was 23 when it all started. She?s 28 now and still curating objects that invoke memories of a sometimes troubled, sometimes pleasant past. A past whose history is the shared history of the subcontinent and the price we paid for freedom.

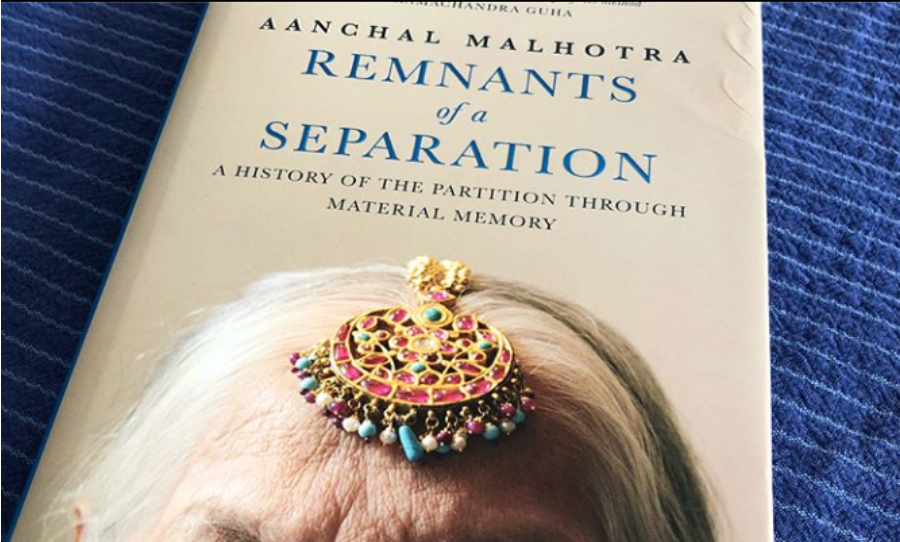

Malhotra?s book with her grandmother?s maang tikka on the cover; Photo: Silver Talkies

The Project

Malhotra?s project includes her first book, Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory (HarperCollins India, 2017), which is the story of the belongings refugees from either side of the border carried with them during the partition of India in 1947. A paperback version would be out soon with more stories and interviews. The book has 19 chapters, narrated to Malhotra by people from both India and Pakistan, with emotions that are often brought to surface after years of hibernation.

?I told you not to revisit the times gone by, but now it is all before my eyes. Malakwal, Qadirabad, the cotton factory, the police station, Kingsway Camp. I know that it will never leave me, but there is no point in being consumed by the past,? Malhotra?s late grandfather Balraj Bahri tells her in one of the chapters.

Malhotra had heard him talk about the hardships the family faced as refugees many times in passing but it is only when he shared his story that she was able to grasp the heartbreak that still stayed within him.

The same heartbreak and a yearning for homes and a way of life left behind appears in several other chapters, the emotions unveiled through the objects that have moved with the family or has been retrieved by them and which they hold dear, knowingly or simply because these had been in their possession for years.

Her grandfather?s utensils that came from Malakwal

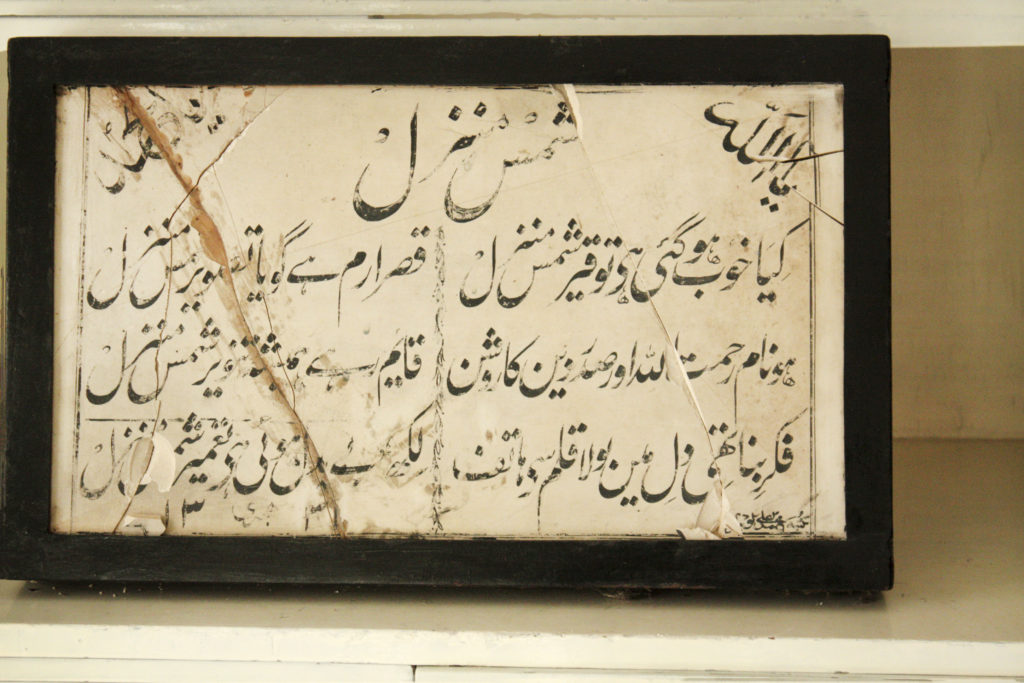

In Lahore, Pakistan, Mian Faiz Rabbani shows Malhotra an old stone plaque that belonged to Shams Manzil, the house he left behind in Jullundur during partition. It was brought back by his niece on a visit in 2008.

?It was as if a long-lost part of me had been returned,? the old man tells her. ?We had resigned ourselves to Partition. But on touching this stone after nearly six decades, whatever the Divide had managed to destroy within me came back to life?.Jullundur was already here with me, in this house, contained in this rectangular stone plaque.?

One thing that often stands out throughout Malhotra?s book is the lack of immense grudge or misgiving. ?There is little or much less hatred towards the ?other? than how we are shown the ?other? in the media these days,? she says. It?s something Malhotra feels is important to highlight in today?s times. ?This is the only way to go beyond fortified borders.? She feels by sharing stories like these, over time probably children in schools and colleges won?t get swayed along communal lines.

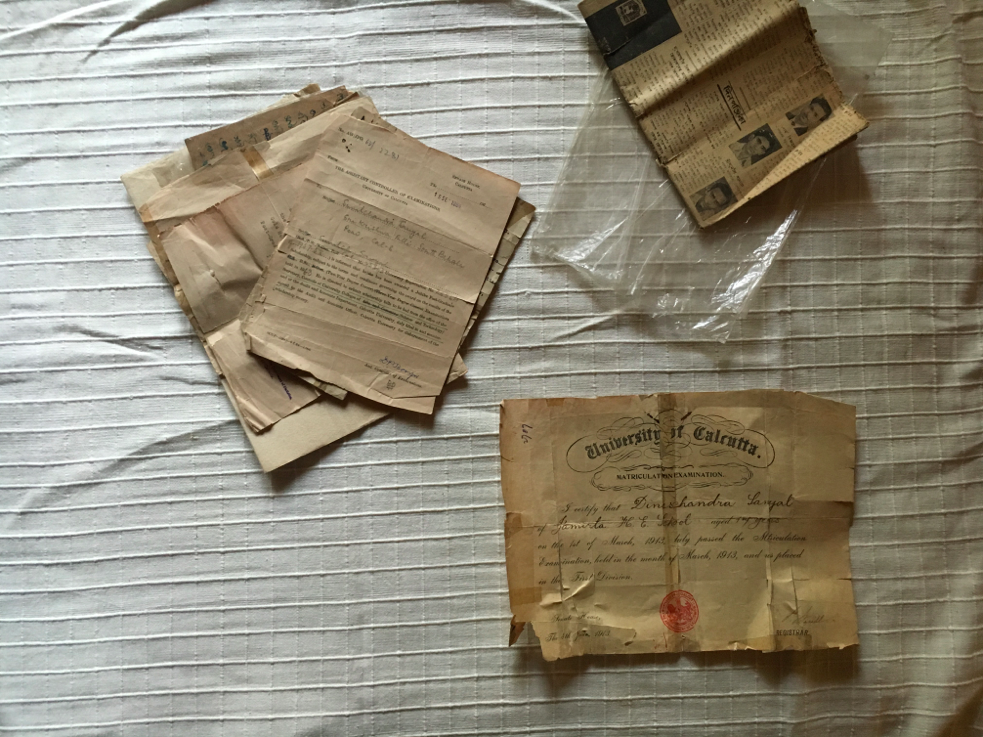

Certificates carried across the border

Malhotra is also the co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory, a ?digital repository of material culture and memory from the Indian subcontinent. While it?s a digital museum, she has smartly tapped into social media to publicise the stories and interest the younger generation though Instagram. Malhotra points out that this is not a museum only of Partition. ?It is a digital museum recording and archiving stories of objects of age not limited to the period of partition, but extending before and after it.?

Interestingly enough, her Instagram account @museumofmaterialmemory has followers who are far removed from the period she is documenting, a proof that history can be interesting and immersive, when told in a way that brings it alive and adds meaning to dates and events. It is also a way for individuals to share their own history. Malhotra feels these stories of how people lived and crossed over to either side are important, even after 72 years of Independence because ?Kids are not encouraged to ask questions beyond textbooks.?

Asking For Memories

Finding objects associated with bittersweet memories wasn?t an easy task for Malhotra. Initially she asked among family and friends, with her aunt even stopping people during her morning walks to ask if they had carried something with them. she was taken on board as a researcher by the Citizens Archive of Pakistan, which helped her find stories across the border. Malhotra was and is extremely careful how she documents the memories shared with her. ?I?m very careful of the memory and the context that you say it in. I?m respectful of the relevance and that?s why I?m in every chapter, listening.?

Jewellery was often carried along

The entire project has been a journey in self-learning for Malhotra. ?I had never studied History. How do you class the weight of historical experience?? Today, after years of interviews, she is a proficient listener and by her own admission, more comfortable in a room with a 90-year-old conversing in Hindi and Urdu than with her own millennial generation.

The interviews weren?t always easy to conduct, Malhotra tells us. The focus was ostensibly an object, though she never had any doubt that the conversation would shift to something else. ?How do you ask people to tell you the worst thing that has happened to them? The difficult part was I knew I was sometimes causing pain to the person but I continued asking questions.? It often took Malhotra several hours of sitting with people to get their stories. What she got in return was immensely rewarding. ?I was listening to stories I?d never heard before. I?d think how?s it possible I?ve never read about this in school. All these stories were not about violence but also of friendships between communities and how people lived.?

She feels one of the reasons people opened up to her was because she was young, almost a granddaughter?s age for most of the people she spoke to. It could also be one of the reasons why there are many young people behind some recent projects trying to archive South Asian history. The distance that the third generation has from these traumatic incidents helps. ?My granddad was always saying we must look forward. Looking back at the past was a luxury the first generation that had lived through these experiences could not afford. They were busy rebuilding their lives! Our generation has the distance and education and the ability to see it from the outside.?

There is also the realisation that this generation with the experiences won?t live for much longer. ?It?s important to collect these memories now or else these experiences will die in silence.?

You can find Aanchal Malhotra?s book and work here:

https://www.aanchalmalhotra.com/

Photographs courtesy: Aanchal Malhotra

Comments

Anonoymous

14 Aug, 2019

[…] historian, multimedia artist and author Aanchal Malhotra’s work includes her first book, Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory (HarperCollins India, 2017), which is the story of the belongings refugees from either side of the […]

Arun Bhatia

15 Aug, 2018

Good review of a good book. Such an innovative angle (objects) to bring the past alive.

You may like to read:

People and stories

Defying borders with Indian classical music: From Indian subcontinent to Ireland

priyanka borpujari

11 mins read

People and stories

Age is Just a Number While Walking 120 kms on Camino De Santiago

Reshmi Chakraborty

10 mins read

People and stories

Breakfast Serial: Serendipitous breakfasts that would appeal to a king

ramesh mohanrangam

5 mins read

Post a comment