Partition 1947: ?Mataji Says We Have to Move?

Compiled through family albums, home videos, journal entries, and interviews, the book Yarn: An Interwoven Memoir follows the life of Shyama, the author?s grandmother, who was pushed by the Partition, at the age of 10, from Pakistan to India. We bring you an excerpt.

In this chapter of ?Yarn: An Interwoven Memoir?, Shyama learns what it?s like to have one?s life uprooted overnight.

Fatima and her daughter Sulo visited Shyama with empty buckets. The constant supply of water from an outdoor faucet brought many families to Shyama?s home, and it was her responsibility to turn the water on and off, because Muslims could not touch their faucet. While the water poured into their buckets, Shyama sat on the jute-woven charpoy, singing songs with Sulo who, along with her mother, squatted on the ground.

Do kothiya do dvar, hichonnikaliya thanedar

thanedar ne bhinnibheli, hichonnikaliyabuddhatheli

buddhetheli ne paighani, hichonnikalirallitakhani

rallitakhani ne rinikheer, hichonnikaliyaikphakeer

Two houses, two doors, out comes the police officer

The policeman bakes a sugar cake, and out comes the oil man

The old oil man puts a mustard seed in the oil press, and out comes Rali the carpentress

Rali the carpentress cooks some pudding, out comes a hermit.

?Are you coming over for Eid?? Sulo?s large eyes appeared darker because of the kajal that lined the rims of her eyes. Wide cloth ribbon held the edge of her pigtails in place.

?What kind of question is that,? Fatima said, ?Shyama always comes over for Eid.?

?I?ll have to ask Mataji,? Shyama said. Her mother had recently begun reminding Shyama how she was almost a woman. Shyama wondered what that meant.

?Ammi, will you talk to Shyama?s bebe??

?Of course I will. Now get up.?

?Ammi, can we stay for one more song??

?Sulo, get up.?

?Why not??

?Don?t ask so many questions.?

?Just one more song,? Shyama said, ?please??

?Please?? Sulo?s eyes grew even wider with hope.

Fatima looked at her daughter. Shyama knew that look. Mataji used it often. Sulo got up silently.

?See you on Eid, Shyama.?

Once Fatima and Sulo left, dadi came outside with a handful of ash and rubbed the faucets clean.

?Why do you do this, bebe?? Pitaji chided dadi for her discrimination. ?The paltani who takes our old rotis smells,? he reasoned, ?but Fatima keeps herself so clean.? Dadi, silently resolute, continued her cleansing ritual.

Jallan?s people cultivated peace through the maintenance of social hierarchy. Each community knew its place, and this awareness led to unspoken rules of interaction. Intercaste marriage was naturally forbidden, but each group knew precisely the nature of its overlap with other groups. The Jats farmed, the Khatris managed, and the Mahajans lent money. Living in the outskirts of Jallan, the Merasis played the dhol, and the Chureys, isolated in a fringe of shanties, swept the streets. Dadi had something to say about each community, and in these sayings Shyama learned about identity.

?There is no salvation without a spiritual guru, there is no honour without a money lender.?

?A Jat should not be taken as dead until all the death ceremonies are complete.?

?Even if a Merasi child cries, he will cry according to the rules of music.?

?Take nine away from ten, you get one,? Aakash said, chuckling, ?take brains away from man, you get a Sikh son.?

As Khatris, Shyama?s family enjoyed relative privilege in this ladder of Hindus, a privilege that defined their interactions with Muslims. A privilege that was about to be challenged.

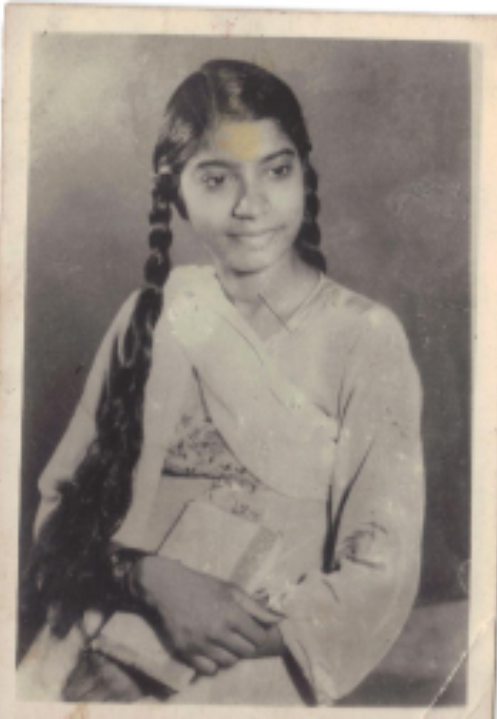

Shyama, before the Partition.

August 1947 rode unsuspectedly into Jallan, redefining unspoken rules overnight. The Hindus of the village suddenly became foreigners, for the country they inhabited was now called Pakistan. Many Hindu families left for India soon after the split, but Shyama?s family, her parents and taya and bua, stayed on, trusting the inter-generational bonds of co-existence. In this time of uncertainty, Shyama visited Fatima and Sulo?s home during Eid.

While Mataji never invited Muslims into their home, Fatima opened her hearth to Shyama and Gopal at every Eid celebration, where Shyama devoured the firini and kalejiyan placed in front of her. The Eid after August 1947 was no different, with one exception. The village seemed emptier.

?Will we have to leave too,? Shyama asked, ?Mataji says we have to move to where the other Hindus are.?

?Ammi, why does Shyama have to leave??

?She doesn?t have to leave. We?ll protect her.?

?Then why are they leaving??

?Stop asking so many questions.?

?You can?t leave,? Sulo said, her mouth stuffed with kalejiyan, ?I still don?t know what happens to Sita after Ram rescues her.?

?And I want to learn all the songs you know.? Shyama looked at Fatima. ?I don?t want to leave.?

?Eat, Shyama,? Fatima whispered, smiling, ?Eat more.?

It was only when Muslims from India arrived in Jallan that Pitaji realised their home was lost.

?The Hindus need to leave,? the recent arrivals told the local Muslims, ?we left our homes so we could move into their homes. If you don?t force them to evacuate, we?ll kill them.?

Pitaji didn?t talk much anymore. After he returned from Hafizabad in the evening, Shyama saw him combing the mane of his horse. Shyama spent this time with her father in silence, as he stroked the horse?s back and combed the horse?s mane. Pitaji washed the horse every morning now, feeding him channa soaked in water. Sometimes, Shyama helped him.

It was decided. They would leave Jallan in ten days. Each migrating family was allotted two iron trunks to take with them. Shyama packed Gopal?s green sweater, her knitting needles, and her wooden box of savings. Why did they have to leave? Why could Fatima and Sulo stay? Who made these new rules? What would happen if she didn?t follow them? Like Sulo, was she asking too many questions? Why did no one have the answers?

On their last day in Jallan, Shyama combed the horse?s black coat and fed him black channa soaked in water. She held his reins one last time. The day?s clackle of wheels and hooves had just begun when Pitaji handed the horse and the carriage to a Muslim neighbour, still believing ? in a tiny pocket of his shaken mind ? that his family would return.

On the morning of their departure, the rules suddenly changed to accommodate only one trunk per family. Mataji unlocked one of the bulky metal boxes, poured its contents onto the street, and burned half of all she had considered important. The alternative, their things being used by Muslims, was worse. As she stared at the flames, Shyama didn?t know which of her items burned.

In this way, when Shyama was ten years old, the Partition uprooted her stability, her childhood, her home. Driving away on a military truck from all she had known, Shyama passed Lahore and along the way, bodies of the discarded dead. Pitaji stared ahead, wheezing and coughing occasionally. Her head covered with a cotton dupatta, Mataji rocked Shyama?s youngest sister Gauri in her arms. Gauri wouldn?t stop crying. Shyama lost track of time.

?Muslims are raping our women,? taya said to no one in particular, ?they are murdering their own neighbours. It is inhuman, the crimes they are committing. So much death.? Dadi began to cry.

?Muslims and Hindus can never live in peace,? Mataji said.

?So much death,? dadi said.

Shyama?s madrassa teacher sat at the inner edge of the truck, whispering a Sikh prayer.

Tumhéchhaadkoeeavarnaadhiyaaoo(n). jo bar chon so tum tépaaoo(n). sevak sikhhamaraitaareeahé. chunchunsatrhamaarémaareeahé.

Aaphaathdaimujhaiubariyai. marankaalkatraasnivariyai. hoojosadaa hamaarépachhaa. sireeasdhujjookariyhorachhaa.

Leaving You, may I never worship another. All my needs, I get from You. You save my Sikhs & Devotees. One-by-One you demolish my foes.

With your Hand guard me. destroy my fear of death. Always side with me. With your Sword protect me.

From Shyama?s receding truck, the dead looked unreal. Had they been killed because they didn?t heed the threats of their new neighbours? Were they caught in a battle of vengeance? Did they die of no fault of their own? Were they Hindu or Muslim?

As one scene left, another arrived. It was like a movie, and she wanted to forget the sad parts. She would never see Sulo again. Who would teach her songs about oilmen and hermits? Would Sulo forget her? Perhaps her dadi and Mataji and taya were right. Perhaps Hindus and Muslims couldn?t be friends. Shyama didn?t entirely comprehend the angry exclamations of her uncle, nor did she have answers for the questions that fizzed in her head. And yet she was sure of one thing ? her life would never be the same again.

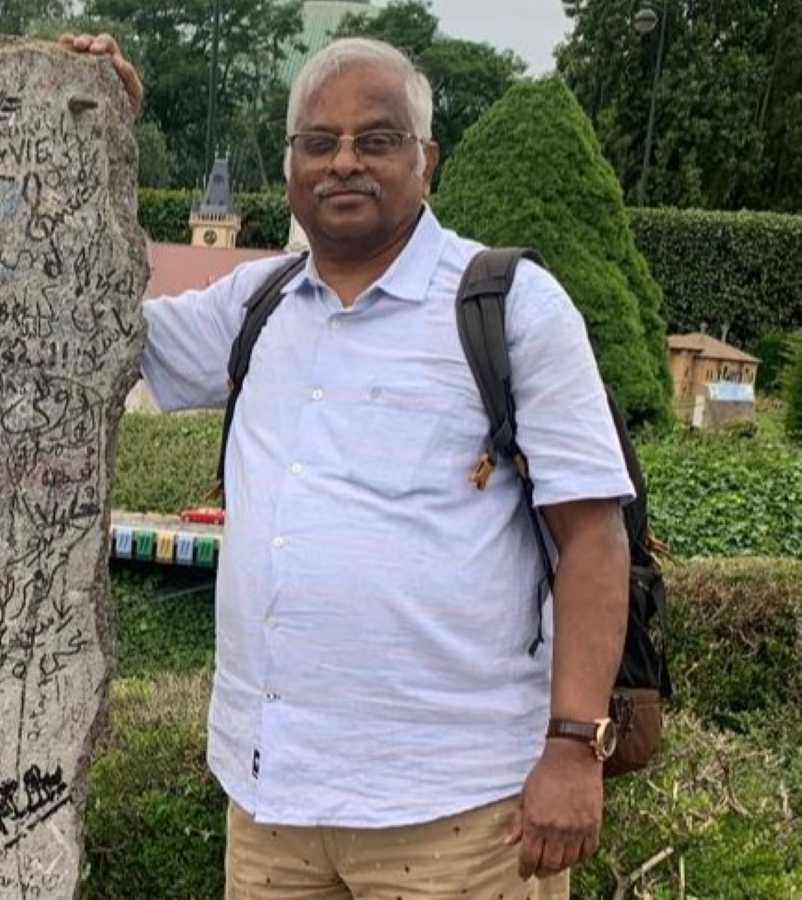

(Featured pic: Shyama, second from left, with her family.)

Yarn: An Interwoven Memoir is available on Amazon. You can also follow Pragya?s work on Facebook.

Comments

You may like to read:

People and stories

Defying borders with Indian classical music: From Indian subcontinent to Ireland

priyanka borpujari

11 mins read

People and stories

Age is Just a Number While Walking 120 kms on Camino De Santiago

Reshmi Chakraborty

10 mins read

People and stories

Breakfast Serial: Serendipitous breakfasts that would appeal to a king

ramesh mohanrangam

5 mins read

Post a comment